By Rhiannon Hoyle at the Wall Street Journal

SYDNEY—The price of iron ore for decades was hammered out in secret talks between the world’s biggest miners and steelmakers.

Now, the dominant force is an obscure commodities market in northeastern China, a stark example of how pricing power for everything from steel to copper is shifting east.

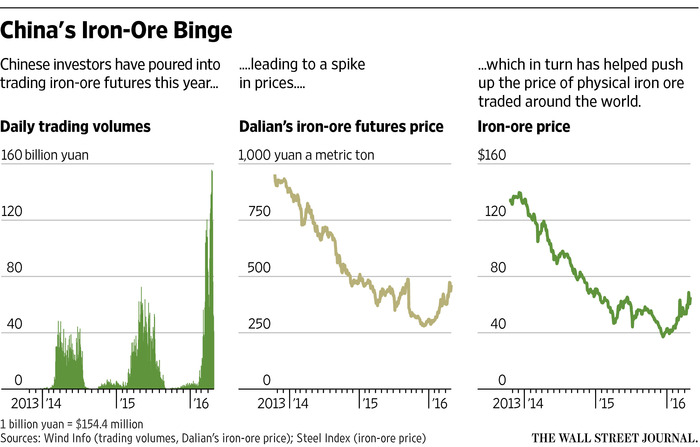

The change has been driven by Chinese investors who have poured billions of dollars intoiron-ore futures traded on the Dalian Commodity Exchange. Their bets, reminiscent oflast year’s frenzy in Chinese stocks, have generated as much dollar volume as gold futures in New York, according to data from Citigroup Inc. They also have created something that had never existed before in the clubby market for iron ore: visible, real-time prices.

Those prices are surging. Despite an expected glut of iron ore in 2016, Dalian iron-ore futures have climbed 46% since the start of the year. Prices for physical iron ore have risen 52%, reaching a 15-month high of $68.70 a metric ton April 21. On Friday, the physical commodity traded at $65.20 a ton, while the most active contract on the Dalian exchange settled at 462 yuan ($70.36) a ton.

The price climb has sparked concern among Chinese regulators and iron-ore producers alike. They fear the speculative frenzy is creating a bubble and volatile conditions that make hedging difficult. Even so, the magnitude of the futures market is proving hard to ignore.

“The volumes that are being traded are so high that they swamp the physical market and are going to be a massive influence on it from now on,” said Nev Power, chief executive of Australia’s Fortescue Metals Group Ltd., the world’s No. 4 exporter of iron ore. “The negative side is the volatility we have seen: It makes it very difficult to predict what the price is going to be going forward.”

About $330 billion of iron-ore futures traded in Dalian in April, more than double the monthly turnover as recently as February and roughly four times the amount spent trading physical iron ore internationally in a year.

The rise in iron-ore prices has underpinned higher steel prices around the world. In the U.S., the benchmark hot-rolled coil index is up 37% this year, to $520 a ton.

In a bid to cool trading in recent days, the Dalian exchange has raised transaction costs and the amount of margin, or deposit, investors must post to trade. Iron-ore futures fell 5.4% Wednesday after declining by the 6% daily trading limit Tuesday. The previous week, futures rose 5.9% on two consecutive days.

On Thursday, the exchange said it banned 13 investors from opening positions temporarily and warned more than 200 clients who violated trading rules.

“All of this growth poses multiple dangers to global commodity pricing stability given how less regulated and therefore less protective the Chinese regimes are for investors, who are perhaps the most speculative in the world,”Citigroup analysts said this past week.

Iron ore was long a desert for investors. The market was dominated by a handful of producers, including BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto, that, until 2010, sold ore directly to steel mills on one-year contracts. Those prices were thrashed out behind closed doors in annual negotiations that set the tone for the rest of the market.

As China’s appetite surged, and steelmakers needed more ore than the biggest producers could provide, that system broke down. Companies started compiling spot prices from surveys of physical cargoes being traded around the world. Eventually, an iron-ore futures market followed.

Iron-ore futures have been traded in Singapore since 2009. While volumes there have also increased recently, they are dwarfed by the contracts changing hands in Dalian.

The rush into China’s commodity markets is shaping up as this year’s version of the 2015 frenzy that sent stock markets in Shanghai and Shenzhen soaring. The binge isn’t confined to iron ore. Trading in futures for steel rebar used in construction has ballooned on the Shanghai Futures Exchange this year, making it the third most-traded contract in the world by dollar volume, behind benchmark New York and London oil futures. Shanghai-traded copper has also been propelled into the top 10, as investors use the metal as a proxy for China’s growth.

There have been similar spikes in markets for agricultural commodities, including corn and eggs, which are traded in Dalian.

Linda Tao, a Shanghai-based trader, is among those who have turned to commodities markets and away from stocks and stock-index futures. Her private-equity firm, which manages over 2 billion yuan ($309 million), delved into iron ore late last year.

“It’s certainly very nerve-racking to watch the evening markets, since we are not sure when a big swing will hit,” said Ms. Tao, who these days takes turns with her colleagues to monitor iron-ore trading late at night. The market is closed to foreigners.

Some investors have been attracted by the relatively low cost of trading commodities futures. Brokers require initial deposits of less than 10% of the value of the futures investors want to trade, compared with a 50% deposit for stock-index futures.

China is the world’s leading consumer of metals from copper to aluminum. The country buys more than two-thirds of all physical iron ore traded internationally, so the signals it sends about demand are closely watched.

Occasional iron-ore price spikes this year testify to the increasing influence of the Dalian futures contract. On March 7, the physical price of iron ore rose 20%, its biggest one-day move ever, according to data provider the Steel Index. That followed an early-morning surge in Dalian, where a huge wave of trading pushed prices up 4.9%, the daily trading limit at that time.

Market watchers said one of the reasons Chinese iron-ore futures are gaining clout is that traders in the physical market can watch them in real time, in contrast with the once-a-day price for physical iron ore, which is published about 6:30 p.m. China time based on an average of physical trades.

“One of the biggest reasons for its influence is because it’s so visible on a high-frequency basis,” said Ivan Szpakowski, who runs North Carolina-based hedge fund Academia Capital.

While demand and supply in the 1.4-billion-ton annual seaborne iron-ore market were roughly in balance last year, Morgan Stanley reckons it will be oversupplied by roughly 60 million tons this year, swelling to 90 million tons in 2017, as mining companies keep production high.

Fortescue’s Mr. Power said he isn’t convinced ore prices will remain at current levels for long. “It is very much a function of trading on the futures market,” he said. “But we are enjoying the price while we can.”

Source: In China, the New Casino is Iron Ore – the Wall Street Journal