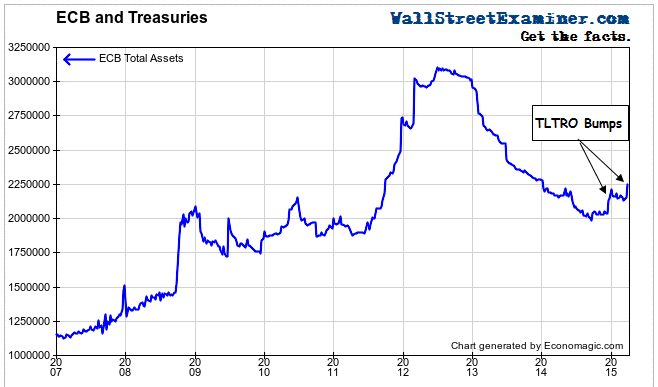

The ECB reported today that it “successfully” purchased €60 billion in bonds in March, meeting its goal under the new QE program. Mainstream finanshill media headlines repeated the “Success!” mantra. However, a closer look at the ECB’s balance sheet data suggests that perhaps that “success” was a hollow one. The balance sheet did expand by €116 billion in March, but €97 billion of that was via a new TLTRO (Targeted Long Term Lending Operation) takedown on March 25. Apparently a net gain of only €19 billion came from the outright asset purchases. That’s because approximately €41 billion of weekly MRO (Main Refinancing Operations) and regular LTRO loans were paid down.

19 billion is barely a rounding error on the ECB’s €2.2 trillion balance sheet. It certainly won’t get the ECB to its goal of growing the balance sheet by a trillion. Nor will 100 billion in quarterly TLTRO, even assuming that the use of that program won’t continue to decline.

I have warned since the announcement of this latest iteration of QE that the banks very well might use the cash to pay down outstanding debt to the ECB. That appears to have happened in March. Banks historically have used funds from ECB long term lending operations to fund carry trades.The TLTRO cash is likely to be used to purchase US Treasuries or other safe securities in a carry trade. Banks are eligible for TLTRO funds as long as they meet minimal targets for loan growth. The ECB effectively has no control over what the banks do with the funds.

As with other central banks’ QE programs, the funds essentially only fund asset price bubbles. It’s a simple case of too much printed money each month chasing a relatively slower growing pool of assets. Wall Street shills call it “appreciation” or “multiple expansion,” but it’s really just a manifestation of inflation, one that conomists ignore.

The fact that the latest TLTRO takedown was “only” €98 billion is notable. It’s about 25% less than the December takedown of €130 billion. Confidence in carry trades or other uses of these funds is beginning to wane. The next TLTRO bump in the ECB’s balance sheet will come when the next round of these operations closes in June. It would not be surprising to see the amount shrink again. In the meantime we’ll get to see in the April and May data just how well the asset purchase program is working to boost the ECB’s balance sheet.

Jim Bach at Money Morning has written a helpful explainer of the complexities of the ECB’s QE program. In the course of that report he rehashed the conomic theory behind QE. Most observers, including otherwise thoughtful analysts, accept this particular conomic theory as gospel. I think that it’s nonsense, and unfortunate that it was included in an otherwise brilliant explainer. Here’s the relevant quote.

It’s important to understand that ECB QE is not “money printing.” And even just by itself, it’s not inflationary.

Here’s how it works. The European Central Bank – or one of the Eurozone member’s national central banks – will transfer a government bond from a commercial bank’s balance sheet to its own. The bond will show up on the asset side of the central bank’s balance sheet. Then the central bank will credit the commercial bank’s reserve account the value of that bond.

The central bank’s balance sheet will increase on the asset side by the value of the bond, and the liabilities by the increase in value of the commercial bank’s reserve account.

But in this transaction, the commercial bank’s balance sheet doesn’t change at all in value, only in composition. It is an asset swap. The commercial bank swaps a less liquid asset (a government bond) for a more liquid asset (euros).

All this does is increase liquidity within the commercial bank. It allows the banks a larger capacity to issue more loans.

As firms and households borrow that money and credit expands, more money is moving around in the economy. This is known as the velocity of money. It’s this velocity that’s supposed to help fight deflation and get dollars moving in the private economy.

In short, QE is an effort to facilitate a higher velocity of money by giving banks more lending capacity.

I would take issue with the statement that “It’s important to understand that ECB QE is not “money printing.” In fact, it is. Even Reuters calls it “money printing” in its stories reporting on the ECB’s balance sheet.

Also, the theory that QE will stimulate velocity is wrong. QE causes velocity to plunge because money supply grows faster than GDP or even potential GDP. Velocity is a derived number, essentially GDP/M. It’s a meaningless construct. As long as central banks are printing mass quantities of money, V will continue to fall. When they stop printing, V will rebound.

As for money printing, where did the ECB (or NCBs) get the funds to buy the bonds? Answer- They printed it. It did not exist before the purchase transaction. The ECB’s balance sheet expanded as a result. Central bank purchases of government bonds during periods when governments are in deficit and financing spending with debt, are quintessential money printing.

The purchase transaction itself does not expand the banks’ balance sheets as Mr. Bach points out, but governments spending the funds they raised with those bond issues does. It’s why US money supply expanded almost precisely dollar for dollar with Fed QE, and why bank balance sheets, and hence money supply, will grow as a result of this program UNLESS the banks use the funds to pay down debt, particularly ECB debt. In that case, both Euro money supply, and the ECB’s total assets will do no better than stagnate.

The ECB only prints the money to buy the paper. After that, it’s out of the ECB’s hands. The ECB has no control over what the banks do with the cash. If the banks opt to use the cash to pay down debt, then the ECB’s program will be an abject failure, just as all its other recent programs have failed to cause its balance sheet to grow. It would be an especially embarrassing failure if the banks use the cash to pay down outstanding ECB credit. The negative deposit rate acts as an incentive for them to do so.

The ECB, with its money printing and negative deposit rates has created, if not a Catch 22, then at least a Gordian knot. QE does not and cannot force banks to lend. Banks can lend whenever they want, without any central bank cash whatsoever. What banks need to make loans is qualified loan demand. Without that, they won’t lend, or if they do, they’ll just create more bad debt.

The only thing QE can do, and does do, is inflate asset prices. The question is how long it will be before the central banks finally grow tired of seeing asset prices inflate into bubbles. The Fed has already reached that point. It has stopped queeing, and is making threatening noises about interest rates (which it can’t deliver on). That leaves the ECB and BoJ. When they finally get exasperated enough by the failure of QE to achieve its stated goals, or worried enough about dangerously bloated asset prices, they will finally pull the plug.

That’s when things will get really ugly.