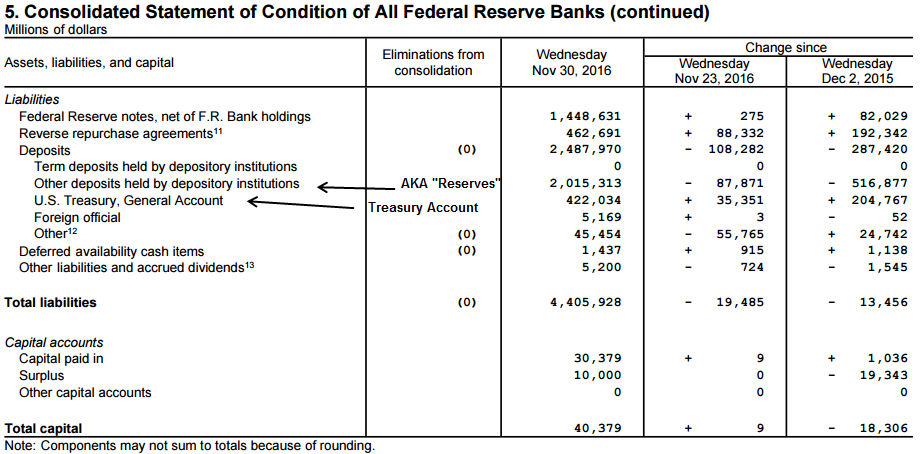

In November, the Treasury’s cash balance in its account at the Fed rose by $50 billion, hitting a record of $422 billion for this date.

Here’s what that looked like on the liability side of the Fed’s balance sheet.

Transfers of money from the bank deposits to the US Treasury account happen when the government collects taxes or sells new debt. If the government holds on to that cash instead of spending it, then the Treasury’s balance in its account at the Fed rises and bank reserves fall.

This causes what is officially known as the “monetary base” to fall. The monetary base is defined to include only cash in circulation and bank reserves, but not US Treasury cash. This is a distinction without a difference. Treasury cash is always available to be spent, and eventually will be. At that point, it goes back into the official monetary base. While it’s on deposit at the Fed it doesn’t count as part of the base. It’s a technicality that can result in the impression that the monetary base is shrinking.

On the other hand, when the amount of Treasury cash at the Fed grows materially as it has over the past two years, the effect is similar to what would occur if the Fed shrank its balance sheet by selling assets.

When the Fed sells assets it permanently reduces bank reserves, and hence the monetary base. That’s because the banks must pay for the bonds the Fed is selling to them with their reserve deposits at the Fed. So bank reserves and the monetary base shrink. However, those actions are semi permanent, while the Treasury will almost certainly spend its excess cash at some point, probably within the next 6 months.

The US Treasury’s deposits at the Fed rose by $50 billion in the past month. This leaves the Treasury’s cash balance at a record for this date at $422 billion, which is $205 billion higher than the same week a year ago.

This is part of the buildup of a contingency fund that the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee (TBAC) recommended that the Treasury build up as a contingency fund for future emergencies. The TBAC is a committee of Primary Dealer bigwigs that advises the US Treasury on how much new debt it will need to borrow in the current and coming quarter. It also advises the Treasury on other specific issues the Treasury requests.

This cash fund which the Treasury has built will likely be needed when the Federal debt ceiling is reinstated in March.

The question is how contentious the negotiations between the Trump Administration and Congress will be to lift the ceiling and how long they’ll drag on.

The question is how contentious the negotiations between the Trump Administration and Congress will be to lift the ceiling and how long they’ll drag on. During that time, watch the pundits becoming increasingly shrill about the negative impact on the market.

While that farce is under way, the Treasury will need to spend some or all of that contingency fund. That will allow up to 6-7 months of gnashing of teeth in the next episode of “Debt Ceiling- The Monster Above.”

During that period there will be no progress on making a deal to increase the debt ceiling. Then at the 11th hour, once the fund is exhausted, another deal will be struck so that there’s no government shutdown, and so that Trump can undertake his infrastructure spending programs.

As in investor, you need to be cognizant of this, because these dramas play out the opposite of the way most people expect. The stock market tends to rise as the drama unfolds because the Treasury can’t sell debt securities. That takes paper out of the supply stream.

At the same time, the Treasury pays off maturing paper. That puts cash back into the pockets of the erstwhile owners of the paper. Many of those holders are dealers and hedge funds who don’t like to hold cash in their inventory. So they find places to stash it, or to actively manage it for trading profits.

Therefore as the crisis plays out, there’s less supply of Treasury paper to compete with other investment securities. At the same time, there’s more cash around as the Treasury spends its rainy day fund to pay off maturing debt. That’s an incendiary package that can lead to both a short term decline in bond yields and a stock market blowoff.

Once the deal is struck, next comes the adjustment back to reality. The Treasury will need to rebuild its cash and borrow more to support old and new spending programs. It will flood the market with new supply and suck up that excess cash it poured into the market as the crisis was unfolding.

If this scenario begins to play out as I have outlined, beware of the crowd warning about its effect on the markets. Those effects are likely to be exactly the opposite of what Wall Street pundits and reporters tell you.

If I still held long positions today, I would probably hold on to them until a debt deal was struck, then I’d clear the decks for the next big move to the downside. I would also be putting on short positions to take advantage of that next selloff. As I’ve discussed elsewhere, it could be YOOGE!

To put it simply, “Sell the news!”—the news of a debt ceiling deal.

Transfers of money from the bank deposits to the US Treasury account happen when the government collects taxes or sells new debt. If the government holds on to that cash instead of spending it, then the Treasury’s balance in its account at the Fed rises and bank reserves fall.

This post is an excerpt from my Wall Street Examiner Pro Trader monthly update on the Fed balance sheet and other banking indicators and their impact on the stock and bond markets. These reports are in the Macro Liquidity service. I first reported in 2002 that Fed actions were driving US stock prices. I have tracked and reported on that relationship for my subscribers ever since. Try these groundbreaking reports on the Fed and the monetary forces that drive market trends for 3 months risk free, with a full money back guarantee. Be in the know. Subscribe now, risk free!