Via Jim Quinn and Zerohedge

Greece is saved!!! I mean BANKERS are saved!!! The market will celebrate the total capitulation of Greece to the EU bankers. Nothing has been resolved. The debt won’t be repaid. The can has been kicked again. Portugal, Spain, Italy, Ireland and even France are essentially insolvent. It’s all a ponzi scheme. The bankers win and the people lose. Hope is not a strategy. Hussman’s weekly tome shows how a crisis plays out. Bad shit happens and the powers that be react with bad solutions that keep their wealth and power protected. Their bad solutions lead to a worse crisis. More bad solutions. And so on, until complete collapse.

Look back to the 2007-2009 market collapse, and you’ll notice something. Despite repeated monetary and fiscal interventions, a positive shift in market internals didn’t happen until March-April 2009. In hindsight, it was none of those interventions that produced the shift, but instead the change in accounting rule FAS 157 in the second week of March 2009 that finally ended the collapse. That accounting change eliminated the “mark-to-market” rule that had required banks to report the value of their assets at market value, and instead allowed banks considerable discretion to choose the value at which those assets were reported. With the stroke of a pen, banks that were insolvent on a mark-to-market basis became whole on a mark-to-model basis. In hindsight, regulatory authorities used that change to abandon any further action that might have put those insolvent banks and financial institutions into receivership or conservatorship. In the end, it was not monetary easing, nor troubled-asset relief, that ended the collapse. It was a change in accounting rules.

A similar failure of memory seems to prevail when the media incorrectly suggests that the collapse of the market in 2008 began with the Lehman bankruptcy on September 15. The fact is that the market fully recovered to even higher levels the following week as the government banned short selling of financial stocks (much like China is doing more broadly at present). Weeks later, in a wicked case of “sell the news,” the actual collapse started literally 15 seconds after the TARP bailout was passed by Congress. Investors want to tie market outcomes to very specific events or catalysts. But history suggests a different lesson: once extreme valuations are joined by a shift toward risk-aversion among investors, the specific events become irrelevant. One way or another, the market is likely to get hit by a truck.

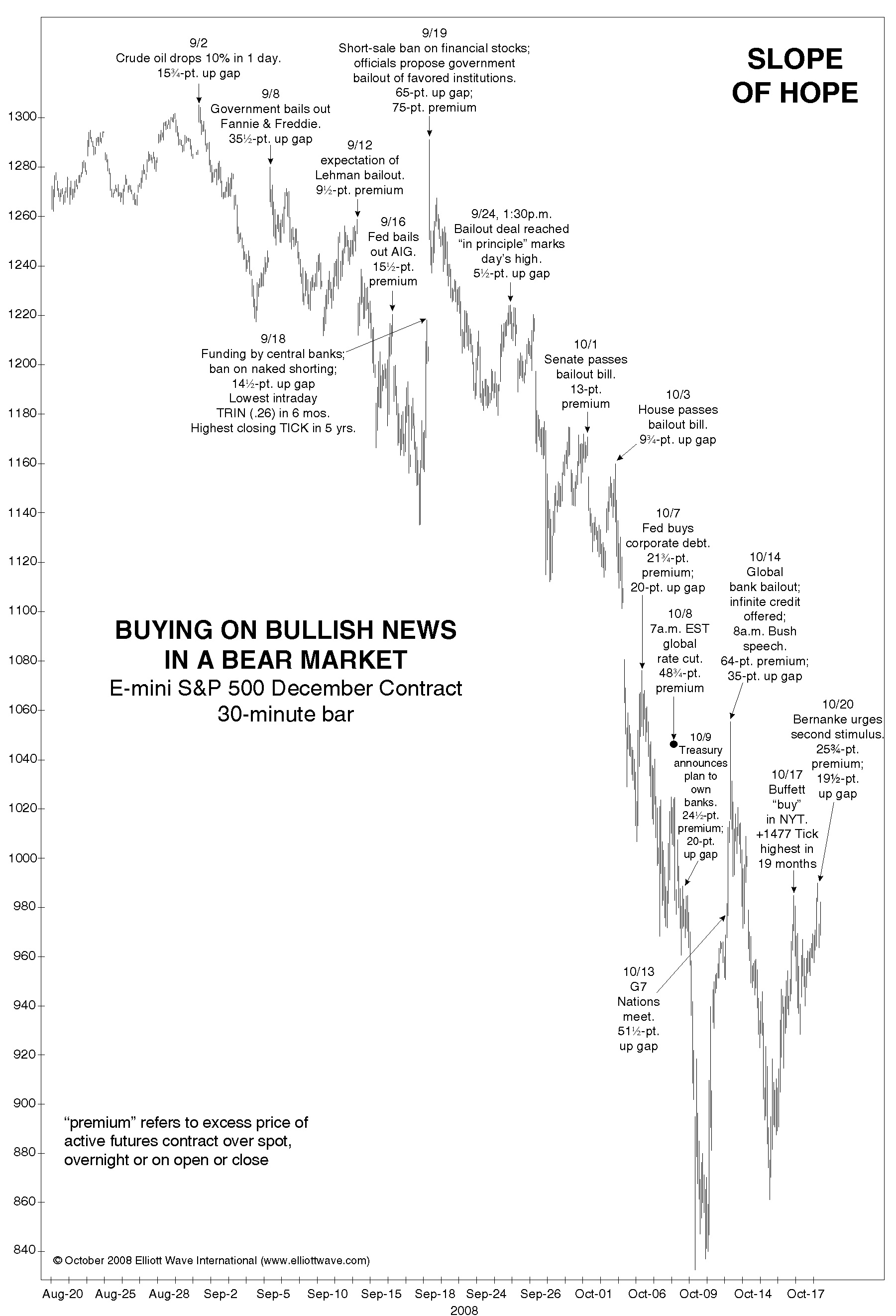

In October 2008, as the global financial crisis was in full force, Robert Prechter of EWT published a very instructive graphic illustrating how the accumulating market losses were descending along a “slope of hope” (the corollary to bull markets climbing a so-called “wall of worry”) despite repeated official interventions. Notice that aside from very short-term rallies following various interventions, the market kept collapsing. We encourage investors to learn from this now.

The S&P 500 would ultimately plunge below 700 by March 2009. Importantly, investors who “followed the Fed” during the 2007-2009 collapse would have done so through the 55% loss in the S&P 500, because the Fed began easing weeks before the 2007 peak, and kept easing all the way down. As in every other market cycle across history, it was far better to follow the condition of investor risk-preferences directly.

Don’t make the mistake of getting the relationship between monetary interventions and the risk-preferences of investors backwards. Monetary easing and other interventions can be very effective when they occur against a backdrop of risk-seeking investor preferences, but history shows that they regularly fail when they occur against a backdrop of risk-aversion among investors. The best measure of investor risk preferences is the uniformity or divergence of market internals across a broad range of risk-sensitive securities. Prechter describes the prevailing psychology of investors with the term “socioeconomic orientation,” and his observations on this, I think, are exactly correct:

“People keep asking, ‘What effect will the next central-bank plan have on the stock market’s behavior?’ This is the wrong question. The socioeconomic orientation turns the question around: ‘What effect will the next stock market move have on the central bank’s behavior?’ Just study [the chart above] and you can see that the authorities are not pushing the stock market around; the stock market is pushing the authorities around. Sadly, when markets push authorities around, authorities push people around. All it does is make things worse.”