It is hard to believe that this past weekend marked the seventh anniversary of the paradigm shift in global financial function. Everything that has occurred in the years since can be traced to those days in August 2007 when money markets broke down for the first time. Even the current, though measured, move away from the US dollar in global trade is as much a downstream event of then as anything else. Careful examination reveals that it was the eurodollar system, linked to trade and financialism, that has wrought such persisting havoc and malaise.

It has yet to be fully digested how much the 2008 panic was centered in London rather than NYC or Wall Street. We know all about Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers, but hidden is the vicarious pathways through which even American banks were depending on their London subs for both funding and to offer themselves alleviation from regulation. Eurodollars represented the “Wild West” of finance; boosted out of the “necessity” (created by profligate governments) to find an alternative to the gold standard which proved too much of a restraint on command.

What was supposed to be a liquidity system that would serve as the foundation of global trade became just another financial tool. In 1985, the Chicago Board of Trade began offering eurodollar futures and interest rate swaps (both are closely linked) and both became very quickly the most traded “products” in history. It is not coincidence, in my analysis, that the eurodollar market itself “evolved” from focused almost exclusively on global trade (gold standard replacement) to asset-based debt and credit production at exactly that moment. Financialization so often breeds the obliteration of self-restraint or limitations that would normally keep such tools contained and focused.

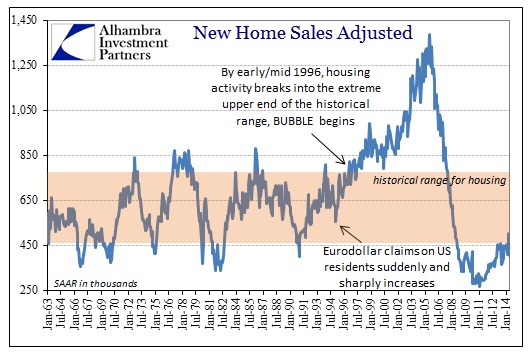

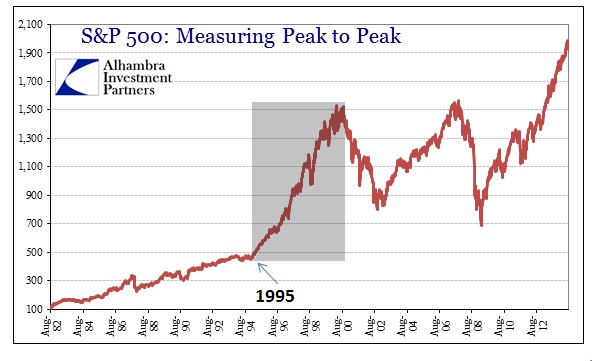

By 1995, eurodollars were marginally more utilized in sowing the seeds of asset bubbles than anything to do with trade, though both, as we see now, were intricately linked. What was also apparent was how much policymakers in the US and elsewhere noted them, loosely and often with hidden meaning, as a companion tool to the monetarist impulse toward soft central planning. In 1990, the Federal Reserve finally relented and removed all reserve requirements from eurodollar liabilities of banking (another instance of Greenspanism).

Where the asset bubble trajectories are evident and obvious, less well-known, even today, are the imprints in global financial plumbing. That was the problem, as the system grew as immense as it did without anyone “in charge” really bothering to take a look at how and why things were the way they were. All that mattered to the FOMC was a particular correlation between debt production, debt accumulation and short-term economic results. How all that was related, and how that “money” was corrosive (decidedly not neutral) was unimportant as long as the correlation seemingly held firm.

But it was already under pressure once the dot-com bubble burst, as the debt-finance surge was far less efficient in the second bubble than the first (and it wasn’t as if the initial bubble period in the late 1990’s was all that efficient in the first place). It took a massive intrusion of finance just to generate what was really an unsatisfactory economic pace, and not just in labor growth and wages. That was all hidden, however, because “everyone” loves asset bubbles on the way up.

But the inefficiency should have been far more concerning to those attempting such economic control. Instead, on September 18, 2007, we got this:

MR. FISHER. May I ask one more question, Mr. Chairman? At the last meeting I asked about commercial paper risk in Europe and got nods of not a great risk. Is there anything that you see or that you can think of that we don’t know or that hasn’t been in this presentation that would indicate significant potential for risk?

MR. DUDLEY. I would hesitate to say that I know with any great clarity that there’s nothing else there in Europe. I think we have all been a bit surprised by the size of some of the conduits that some European banks were sponsoring relative to their capital. I would be very hesitant to say that we have transparency regarding that marketplace and know with certainty that there’s nothing else there.

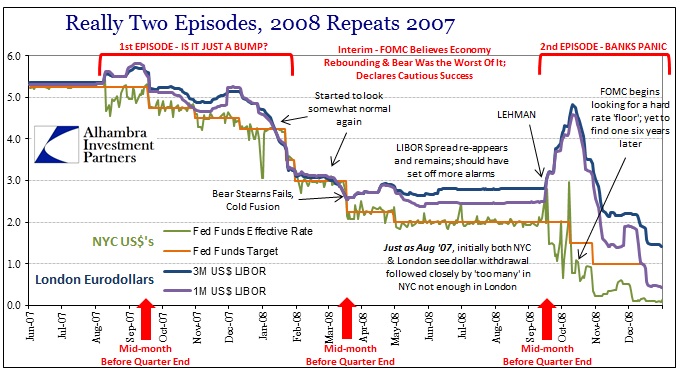

A little more than a month prior to that meeting there was a major disruption in interbank funding markets. Describing the “carnage” in words leaves a lot to be desired, as 3-month LIBOR on August 9 “skyrocketed” from 5.38% to 5.50%. As I said, in words it sounds like so very little, but viewed in context the great chasm between “what was” and “what is” is clear as day:

On the “emergency” conference call of August 10, 2007, Bill Dudley again referred to the European problem without specifically recognizing it as a symptom of the “evolution” of banking and credit up to that point (which is why he was so “surprised” in September).

DUDLEY. In addition, there’s a tremendous amount of focus on the commercial paper market. The European commercial paper market is not doing well at all, and that’s really one reason that you’re seeing the European banks scramble for funding.

I talked to a dealer this morning in the U.S. commercial paper market. I guess the way I would characterize the situation is that the U.S. commercial paper market is continuing to function but at a very tough level of functionality. People are shortening up. They are starting to take names off their lists of programs they’ll invest with. The asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) market is the area of greatest stress.

That was the symptom, yes, but it gets the analysis totally wrong – and the FOMC would remain in that dark for the remainder of the crisis period. The target on ABCP was European because of the geographical divide that was there simply due to this NYC- London, US$/Eurodollar framework. In short, the financialization of the eurodollar “market” was coming apart in a cosmic fit of irony for the mechanism that replaced the gold standard.

The way that manifested was “too little” dollars available in Europe, specifically London and indicated by LIBOR of whatever tenor, and “too many” dollars on offer in NYC. Thus, the day after August 9, the federal funds rate ran far below target (a big problem, though it may not seem like it) while LIBOR began to run higher and at a far greater spread. While the FOMC and various central banks all around the world coordinated their responses, nearly all of those were 20th century measures in a 21st century world. They did not, indeed could not, handle this systemic fragmentation that was evident only in geography because of the way in which the gold standard was substituted by eurodollars.

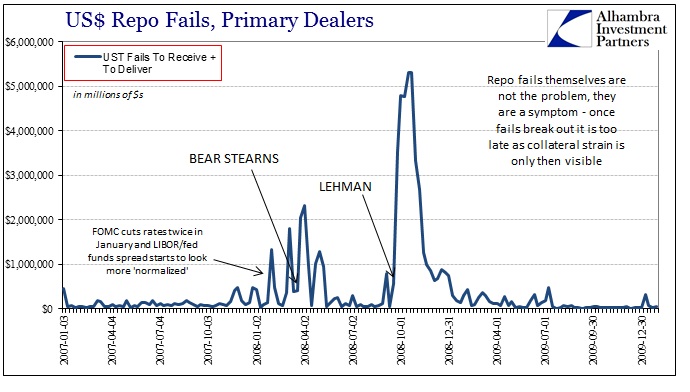

The crisis period itself was really two, separated by a seeming calm engineered by the heaviest monetarism ever seen (to that point). And I should probably be more specific in that the “calm” period itself was broken into two distinct parts, with interbank unsecured markets looking more normal by January 2008, particularly as the FOMC initiated not one but two rate cuts that month. But such calm was just on the surface, as retreat in eurodollars was matched, if not surpassed, by repo strains.

The massive unwind in MBS markets meant a huge rush for collateral without any way to alleviate the shortage – traditional monetary measures through the Open Market Desk were wholly ineffective because they depended on the primary dealers to circulate any additional “flow”, which the primary dealers refused to do on an unsecured basis. Without widely available collateral, there was a dual-problem of flow in both unsecured eurodollars and repo. That was what caught Bear Stearns eventually (preceded in the weeks before by a few more hedge funds that should have been more of a warning about plumbing), which actually began the second phase of the interim “calm” period. In light of that event, the appearance of calm in LIBOR and elsewhere was highly misleading, indicating deeper problems.

In that second part, the FOMC saw Bear Stearn’s failure as the nadir, the worst case. From that point forward they began to see signs of hope and optimism in not just financial function but the economy. Yet, like the first part, it was an illusion that was evident to anyone actually looking in the right place.

For one, the geographic divide was opened once more with Bear’s demise, never to reclose during the panic. That was a systemic hint that nothing was “resolved” nor was it on the road to such. While the FOMC focused on LIBOR/OIS and others, their intentions were credit spreads as if they could figure out “stress” in the system by the usual indications. But this was not a typical bump in the road, it was a paradigm shift of eurodollar corruption out entirely of the mortgage debt business, or what had been the FOMC’s primary conduit for “defeating the business cycle” inside the US. MBS was no longer usable “good” collateral, so the entire system was imploding and the geographical spread showed as much all throughout the second part of that interim “calm period.”

By the time Lehman failed in September, the FOMC was “unlucky” enough to be behind the curve not once but twice, as funding markets suddenly linked with repo problems into something that was as much a panic as anything else. However, this was history’s first instance of a bank panic consisting solely of banks panicking. There was no widespread “deflation” threat of ATM’s running out of currency; in fact, outside of IndyMac and a few limited occurrences there was nothing of the mythical deposit-currency retrenchment at all (Milton Friedman’s monetarist explanation of the Great Depression).

Why bring all this up, particularly after seven full years now? The first reason is simple, since from then on we have seen an absolute intrusion into market function of historic proportions and all in the name of “stimulus.” To what gain? We got the Great Recession anyway in spite of it all; and nothing like a recovery afterward. The very reasons for total market repression were born that day in August 2007, to be repeated at every questionable instance (like September 2008 when there was no real panic outside of banks).

Second, and perhaps more important with regard to the future, the FOMC demonstrated both a blindspot and a curious ignorance about the systemic weaknesses of “its” financial system. The crisis period shows not just one limited instance of the feebleness of monetary response, but rather the template by which monetarists will fail time and again. When you are captured by systemic ideology, you will never see the cracks in that system from looking inside out.

We are told that the liquidity system has been repaired in the years since, but we know that to be false, not just in the failure to create a durable interbank rate floor, but by the persistent and regular repo market fragility. It is a signal of systemic bottlenecks or weakness that is the very same manner by which the paradigm began to shift the first time.

Like the surprise over the “size of some of the conduits that some European banks were sponsoring” back then, does anyone have real confidence that they will not be surprised again, this time likely over leveraged lending and junk debt. There may not be an immense mortgage bubble held over financialism, but that does not mean financialism has been repressed with the systemic rate of risk. As we see with Europe, sovereign and government debt can be as much a problem if not more so than “private” debt obligations. There is more debt now than at any moment in world history, however you wish to scale it.

From August 9, 2007, forward, every irregularity has been used as an excuse for the exercise of total control and all in the name of trying to preserve a paradigm that no longer exists. The FOMC wishes to recreate the mid-2000’s without having an ability to do so – which shows both the dangerous nature of their goals and again their ignorance about exactly how to achieve them.

However, despite all of that, the anniversary date is important as it marks the point at which the eurodollar standard ceased ubiquity. It had been, to that point, unquestioned through several crisis periods and thus built a reputation and expectation for durability and function. Since then, not only did it gain interruption, it has done so on a few highly visible and dissatisfactory occasions (2011 and 2013) while at the same time being bastardized by QE and the like. What was supposed to replace gold in a regime of monetarist flexibility has been shown as uniquely worse because the rules constantly change without any of the limiting benefits once received by gold’s “rules of the game.”

In other words, we are now seven full years into the next regime, though we have yet to receive any clarity on what that will finally look like. The big question is whether our arrival will be by way of intentional reform, or another episode like that of 2007-08. But as I have plainly shown here, there really is no going back.

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

“Wealth preservation and accumulation through thoughtful investing.”

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, contact us at: jhudak@alhambrapartners.com