The primary argument in favor of “aggregate demand” policies, or at least attempts at demand-side “stimulus”, amounts to putting more money into the economy as spending. You hear it all the time, as in give money to people that do not have it now and they will spend it, thus creating a “pump priming” that stirs the economic engine as a whole to full health and circulation. In other words, spending begets more spending, and then investment and so on.

That is the basis for the idea of government programs like unemployment insurance payments as a “stimulus.” As we saw from retail sales this morning, there is an empirical problem on the way to confirming that theory. Auto sales have been the one shining, bright star as it relates to the monetary channel. Yet for all that spending on autos there is no spillover, no broadening of the economic reach. Spending begot nothing. Instead, you can make a plausible case that spending on autos is actually crowding out spending on other big tickets, becoming a net negative.

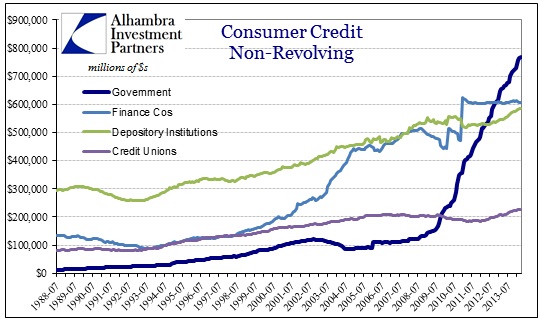

I think it is common knowledge by now that credit in the real economy (financial economy is another story) is running in only two channels – auto loans and student loans. The scale of these monetary facets is growing ever larger, yet there is no apparent “pump priming.”

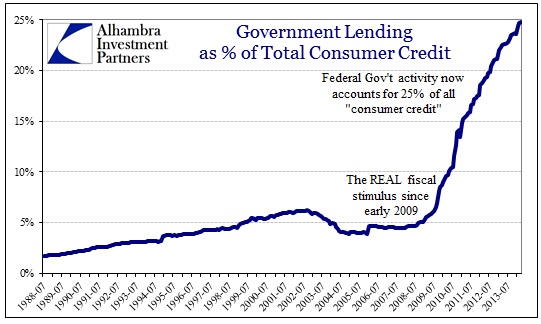

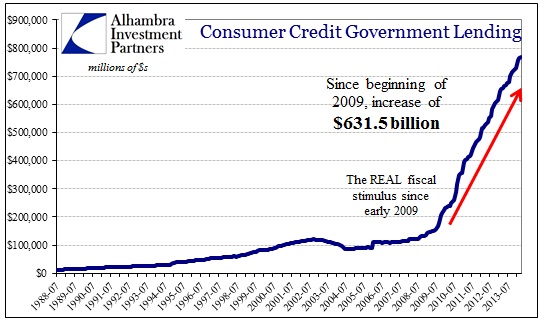

We know the government takeover of student lending has become the de facto fiscal stimulus excess now that the ARRA is long forgotten. It has been sustained and large. In absolute dollar terms, the increase in student loan balances since 2009 is an unbelievable $632 billion.

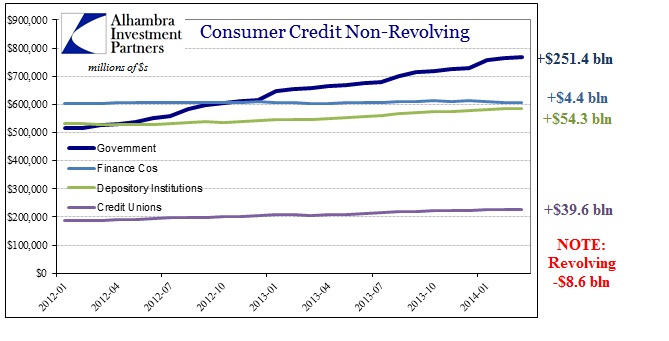

It is interesting to note that contrary to this government program, credit attainment has been far more mixed. In terms of debt usage for direct spending, revolving credit has certainly reached a post-crisis low, but households have been exceedingly reluctant to take on new revolving balances.

In other words, consumers have deleveraged as much as they apparently are going to in this cycle. That leaves only the intrusion through student and auto loans (and mortgage refis to a smaller extent, but that is done).

In the context of the four major providers of consumer credit, finance companies were once the kings of revolving and auto loans but have been completely absent from the “recovery.” That relates to the inability of these specialty vehicles to attract financing after nearly collapsing (and bringing everyone around them down too) in 2007 and 2008 (like GE Capital and some of the auto finance subs, ex Ally/GMAC). Depository banks have participated in the auto loan surge, though I can’t tell how much that is the repatriation of some of the finance company lines (taking up the slack).

Credit unions are the big winners here, filling the breach on the non-revolving side. That means there are plenty of outlets willing to lend into consumer spending appetites, even outside of government. The rate of credit growth is nowhere near what it was pre-crisis, but that has little to do with bank and credit production capacity. And it is not lending standards holding back credit saturation, as subprime auto loans dominate marginally.

The increase in student loans since just the beginning of 2012 is staggering, amounting to a quarter of a trillion in government “stimulus.” Again, autos feature prominently as both depository banks and credit unions have lent freely (+10.2% for banks; 21.1% for credit unions). Yet, during this exact period the economy entered a stubborn and durable slowdown that mimics in many ways a recession. That suggests why this period may not have looked exactly like previous recessions, as there is still a significant shot of credit running into the system but largely (and only) through these artificial channels.

So again, the real economy does not respond to mindless sources of spending, trying to essentially force a pickup in growth over time. Instead, this credit effect is incredibly inefficient to that end.

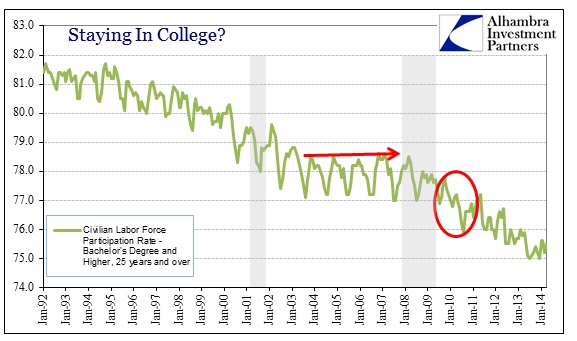

While there are certainly other factors at work here, we can at least note the unquestionable decline in labor participation of those with a bachelor’s degree (and higher) that took place at the end of the Great Recession. That was right around the time when the student loan surge began to take full bloom. The participation rate has only fallen further since that time, more than contradicting the idea of an improving labor market – the timing of these changes coinciding with recession is pretty conclusive about the pre-eminence of the macro explanation.

The overall track of the participation rate has been lower since the 1990’s, but there is no reason to believe that the trend would not have stabilized like it did during the housing bubble when labor and wages were at least luke warm. But since this series includes only some that may be staying in college (advanced degrees and career students) and even retirees, we might instead look at the labor force participation of those between 20 and 24 years old.

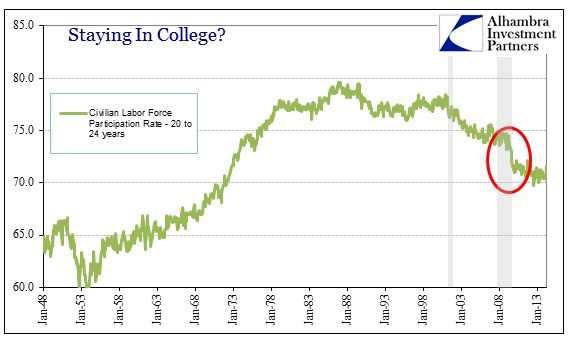

Again, same story. In fact, these results seem to confirm the college lending bubble’s impact since the government’s most forceful intrusions are creations of this century. The labor participation rate was pretty stable throughout the 1980’s and 1990’s, and only began to reverse as student and government lending accelerated sharply.

The net result of this “stimulus” is undoubtedly consumer spending on education. In the fiscal theory, that should increase spending in the whole economy as these student funds (including those not lent) paying tuition “creates” jobs at educational institutions. So where is the spending begetting? More than anything, I think this demonstrates that you can’t create an economic positive by paying people not to work (which is what this amounts to). It disabuses the notion that any spending for the sake of spending (and thus the idea of generic aggregate demand itself) is a net positive.

There are more professors and administrators now then there have ever been, but the growth rate in educational jobs has slowed since 2011 despite the onslaught of credit. Again, this credit-driven bubble is wholly inefficient. If stimulating generic aggregate demand in these manners were at all effective, the economy would be seeing a growing participation rate and actual spending across wider and wider sectors. Instead, as retail sales showed this morning, the economy continues to sink into further despair.

The bottom line is that those “forced” onto the debt transmission only fall further behind. These college kids are taking on more and more debt that ends up raising their requirements for future employment at the same time reducing their future ability to spend freely. That is growing impoverishment in a broad sector that is not balanced out by a true economic recovery.

When Bernanke often testified and spoke about the acknowledged costs of monetarism, he always (always!) followed that idea with, painful as it was for him to admit, the sophism about a growing economy.

“That said, the Committee is aware that a long period of low interest rates has costs and risks. For example, even as low interest rates have helped create jobs and supported the prices of homes and other assets, savers who rely on interest income from savings accounts or government bonds are receiving very low returns. Another cost, one that we take very seriously, is the possibility that very low interest rates, if maintained too long, could undermine financial stability. For example, investors or portfolio managers dissatisfied with low returns may “reach for yield” by taking on more credit risk, duration risk, or leverage…

“Because only a healthy economy can deliver sustainably high real rates of return to savers and investors, the best way to achieve higher returns in the medium term and beyond is for the Federal Reserve–consistent with its congressional mandate–to provide policy accommodation as needed to foster maximum employment and price stability.”

In other words, he felt sorry for seniors living on fixed income as he willingly repressed savings, but that was a “necessary” cost to the positive offset of a debt-driven restoration. Not only that, he freely and haughtily asserts that monetarism and debt is the best way to achieve such an economic revival. But there is no revival, has been no revival and it doesn’t appear to be close at hand; in fact even his former cohorts are giving up on QE’s premise and promise. Will there be an accounting of this decidedly net negative influence? It’s not just students stuck in college that have grown poorer as a result of this “best way.” How much more poverty will be added once the asset inflation subsides and markets break down once more?

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

“Wealth preservation and accumulation through thoughtful investing.”

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, contact us at: jhudak@alhambrapartners.com