Abenomics, the new economic religion of Japan, has kept some of its promises: It created inflation while wages stagnated, thus whittling down real incomes, further squeezed by the broad consumption tax hike. It devalued the yen by 25%, thus vaporizing a quarter of the wealth of the Japanese without having to tell them directly. And to make up for the tax increase on consumers, Abenomics elegantly cut taxes for Japan Inc. Grudging respect is due Prime Minister Shinzo Abe for these noble accomplishments.

In other areas, his record is spotty. One of the goals of his policies was to fire up exports by making them cheaper overseas and reduce imports by making them more expensive to consumers and businesses at home. It would crank up Japan’s manufacturing sector and lead to a trade surplus that would inflate GDP, make Abe a hero, and save Japan.

Exports and trade surpluses have been vital to the Japanese economy. And reconstituting them has been a cornerstone of Abenomics. But that plan has gone to heck.

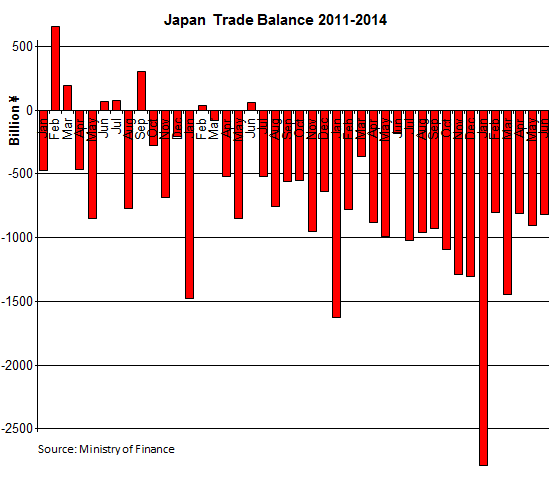

Not step by step, gradually over time, but in monthly leaps, whose size surprised even Abenomics-cynics like me. And the Ministry of Finance rubbed it in today when it published the trade statistics for June.

Exports, instead of soaring due to the watered-down yen, dropped 2.0% from a year ago to ¥5.94 trillion. Imports, instead of dropping due to consumers being squeezed by higher prices and stagnating incomes, soared 8.4% to ¥6.761 trillion. The resulting goods trade deficit jumped to ¥822.2 billion.

It was the worst trade deficit for any June ever. It was over four times as bad as last year’s “worst June deficit ever.” In June 2012, Japan still had a surplus. Historically, June is one of the better months for Japanese trade. But that surplus in June 2012 was Japan’s last. What followed were 24 months of relentlessly deteriorating trade deficits. The worst series in Japan’s recorded history (far ahead of the second-worst, the 14-month period in 1979-1980).

For the first six months this year, compared to the same period last year, the trade deficit soared 57%!

Here is what the flaming success of Abenomics looks like, boiled down to one chart:

The debacle was spread across the board, starting with its largest trading partner, both in terms of exports and imports, China. Since about one-third of Japan’s exports to China get transshipped through Hong Kong, I combine them. So exports to China and Hong Kong edged up 1.6%. But imports from them jumped 10.6%. And the trade surplus in 2013 of ¥57 billion turned into a trade deficit of ¥63 billion. That’s a deterioration of ¥120 billion. Even exports to the US, its second largest trade partner, declined 2.7%, while imports from the US rose 6.8%.

The export declines were spread across the largest categories: transportation equipment (cars, trucks, etc., which account for nearly a quarter of all exports) dropped -0.6%; machinery (about a fifth of all exports) -0.4%; electrical machinery (semiconductors, audio-video equipment, batteries, etc.) -5.1%; manufactured goods (steel products, etc.) -0.2%.

And imports rose across the largest categories. Mineral fuels (petroleum, LNG, coal, etc.), which make up nearly one-third of all imports, rose 8.3%.

I can already hear the voices that blame the imports of LNG and coal required to feed the fossil-fuel power plants that have replaced the capacity of the shut-down nuclear reactors. But wait. Imports of LNG and coal combined totaled ¥749 billion. If Japan hadn’t imported any LNG or coal – which is impossible even with all nuclear power plants running at full tilt – it would still have had a trade deficit of ¥73 billion.

The problem lies in a strategic shift undertaken by Japan Inc. – offshoring – to take advantage of cheap labor in China and elsewhere, though it lagged behind the US in that respect. Japan Inc. accelerated that shift after the 3/11 earthquake and tsunami, when supply chains in Japan collapsed. And when Abenomics came along, they redoubled their efforts at offshoring: the devaluation of the yen allows them to translate revenues and profits from foreign operations into weaker yen, thereby performing paper miracles on their financial statements. And promises of additional devaluations make that incentive to offshore even juicier.

Some of the offshore production is then imported. So imports of the largest categories all rose: electrical machinery up 7.7%, machinery up 14.2%, and manufactured goods up 14.0%. Japanese companies used to excel in these categories. While some have gotten clobbered by international competitors, others still excel at designing and making these products. They just don’t manufacture them in Japan anymore.

Given the incentives that Abenomics gives Japan Inc. to invest and produce overseas, rather than in Japan, these dynamics are unlikely to change direction. And the ballooning trade deficits will become an albatross around the economy’s neck. But don’t expect consumers to jump in enthusiastically and help out. They’re squeezed by stagnating incomes accompanied by inflation and a consumption tax hike – what I call “inflation without compensation.” It knocked their purchasing power overall down by 3.6% for all items, including services, year over year, and by 5.6% for goods. And they’re unlikely to pull Japan out of its post-tax-hike funk anytime soon.